Big science produces a lot of data, and the Future Ocean Cluster is no exception. Its people make use of research vessels, marine vehicles, sensors, laboratory instruments and massive computational infrastructure. Between them, these assets generate many terabytes of data on every aspect of the oceans, from their weather to their chemical composition and temperature, and the life they contain.

But the unique character of the marine sciences in Kiel means that even this is not the full story. The Cluster is now producing data on social, human and cultural aspects of the ocean such as arts, poetry and narratives, including material on the people who live near the sea and the uses they make of it.

We must keep this data as a record of the past that informs present-day research, and as proof that we have conducted sound and reproducible science.

This demand for sophisticated data management grows out of changing requirements for science, and especially for openness in the scientific process. Funding organisations and other sponsors of research now expect data created in the course of publicly-funded projects to be accessible through data archives in a reproducible, comprehensive and public way. This is a big change for the current generation of researchers.

At Kiel, this challenge is being addressed by the implementation of a structured Data Management Plan. Its approach follows the FAIR concept, which is to make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable as soon as possible. The aim is to guarantee that anyone wishing to interpret and create knowledge and information from Kiel data can do so. The plan contains incentives which will motivate young researchers to be serious creators and providers of properly-organised data.

It is critical that all data repositories not only store data files, but also describe them systematically. This initiative involves capturing data in a systematic way as it is created or measured, and placing it into a new and innovative data system which encompasses the acquisition, curation and use of these vast flows of research data in data pipelines. Where have they been gathered? Who recorded them? How was this data collected? When? What instrument was used to gather these numbers, and how was it calibrated? This information, data about data, is called metadata. It is essential if data is to be reused, or if different datasets are to be compared.

In the Internet era, the possibilities for disseminating data are endless. But sound, transparent science needs a single point of "truth and trust," so that marine research data is used in a documented manner in line with established policies, in the knowledge that it will remain available after the lifetime of any individual research project. This development goes beyond today's practice of allocating money for data management to a specific project. We are now creating a single structure which will make our data useful indefinitely for the whole research community and its stakeholders.

Dirk Fleischer from Kiel Marine Sciences recognises that

"topics ranging from the natural sciences to environmental ethics, the social sciences, law, economics and the political sciences require different data strategies." Several side projects have been launched to address these issues on a joint basis, involving the Kiel university library and computer centre alongside research groups across the University and at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel.

People power

This ambition calls for the establishment of a substantial data infrastructure. A core data management team is carrying out this task for the marine sciences in Kiel, and exists on a permanent basis.

To set standards, the team has implemented guidelines which inform the data policies of all Cluster projects. It has also established a platform for data management projects in the marine sciences, and is the point of contact for data management services to individual research projects. In addition, the team helps Kiel Marine Science to work with other data resources. "We support Kiel scientists in archiving their publications and data at the Pangaea world data centre for the Earth sciences, as well as in our own institutional publication repositories, OceanRep and Kielprints." says Carsten Schirnick from the Kiel Data Management Team.

Recent developments include a dedicated media server for images and video data, to store the large volumes of content generated by remotely operated and autonomous vehicles. Biigle, a tool for image and video annotation, has been added to this server and allows researchers to digitally annotate and store pictures and videos from underwater camera systems.

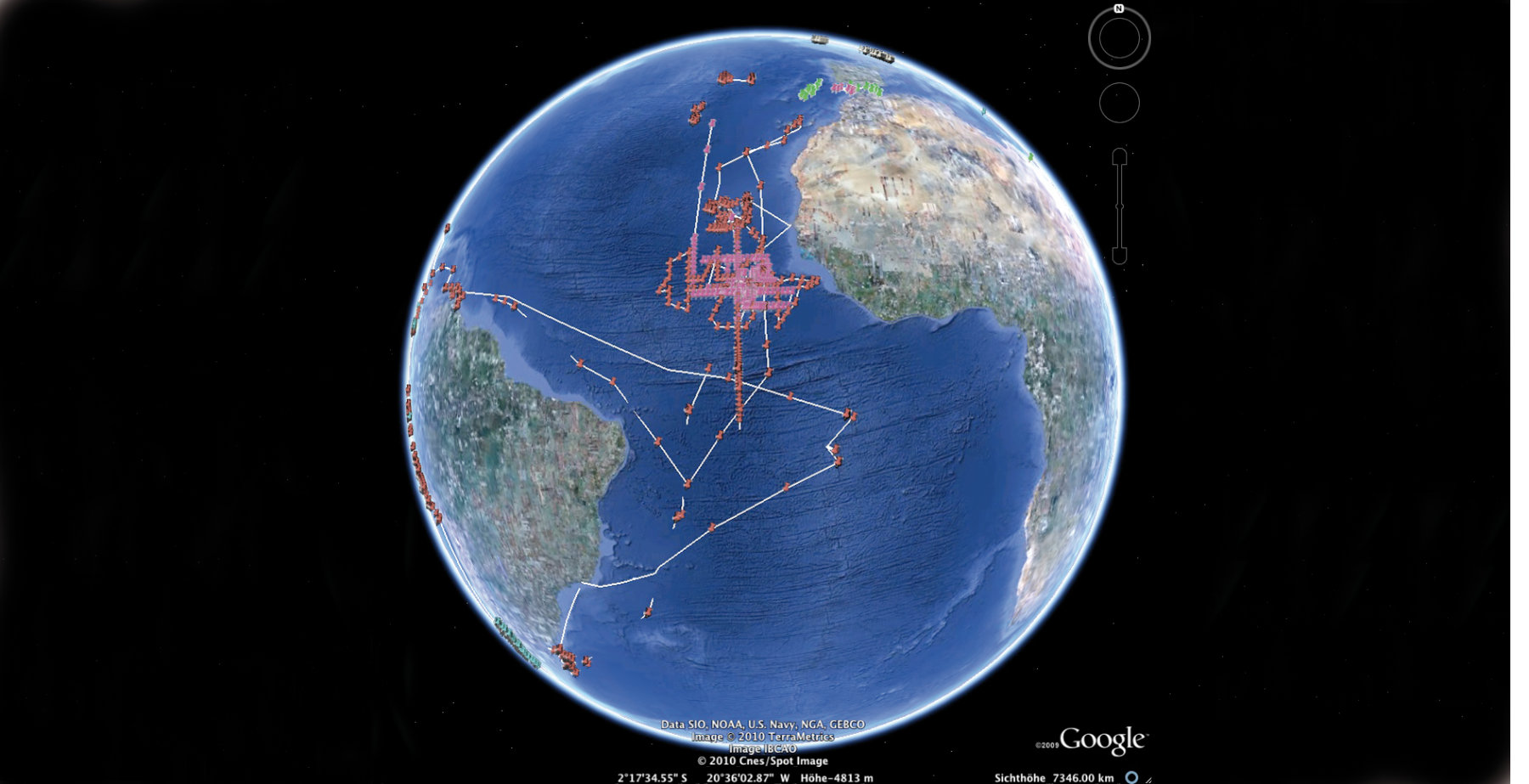

Another benefit of structured data sets is the ability to connect applications to the data repository. As a result, it is now possible to display Kiel's ship expedition data through interfaces such as Google Earth. This is valuable for scientists, but also opens up new possibilities for the public exhibition of complex data. For example, a slider display can be used to show how seawater salinity and temperature have varied over time in some regions of the ocean.

Fleischer stresses the need to educate students as well as staff in the importance of data, through the curriculum and in other ways. "We believe it is possible to create a data environment in the near future which can collect all data generated at a research site in a structured way. To teach the next generation of scientists the value of research data planning, we need to add some twists to our teaching. We could produce research-ready data sets from annually-repeated practical courses, teaching students the value of reused data. That will involve considering students not only as consumers of teaching, but also as being actively involved in research. Their course research could lead to small publications which are only possible if research data has been properly stored and documented. That will demonstrate the benefits of structured work with research data."

At heart, the data management project is about people, not bits and bytes. As database pioneer Jim Gray put it: "May all your problems be technical, we can deal with them. It's the social problems which are the real hard ones." This message is well-understood in Kiel.